Transformers marks your second time as sequence supervisor at ILM. What sequences did you work on?

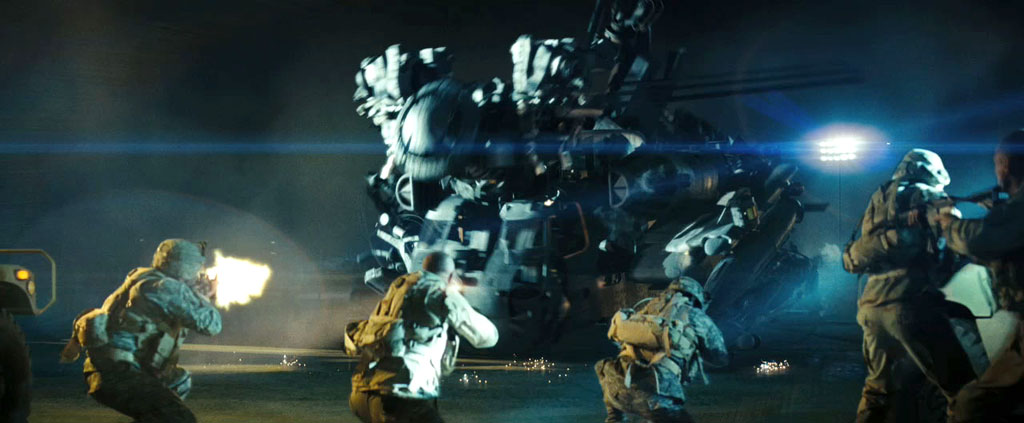

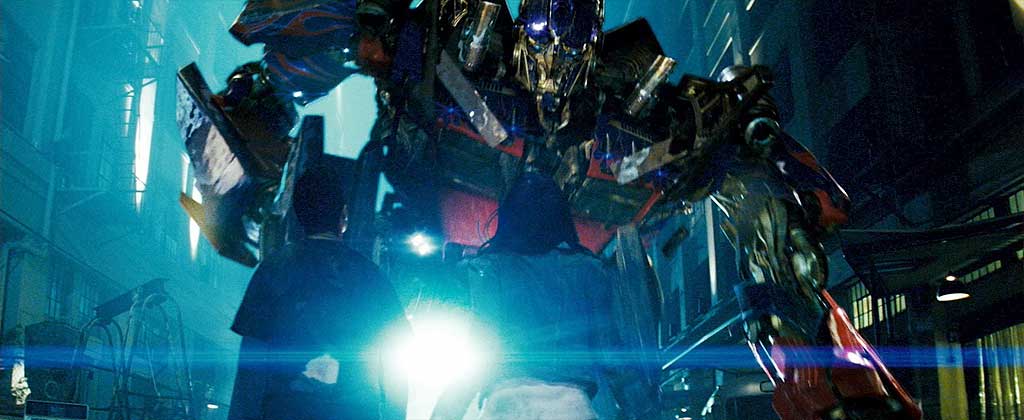

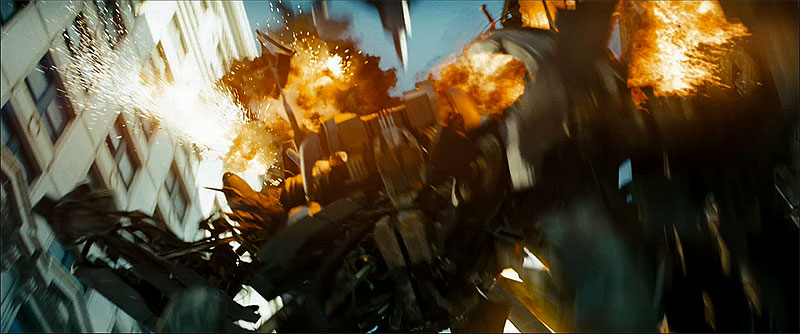

I was sequence supe on the Scorponok desert attack sequence (along with Nigel Sumner), the Blackout attack sequence that begins the film (along with Leandro Estebecorena), and the end battle sequence (along with Nigel and David Hisanaga). The end battle included the last fight between Optimus and Megatron, Blackout getting lazered and destroyed, Starscream attacking the F-22’s, and a few other shots here and there. The shots I personally did were pretty much in those sequences, too, and a few others. It was nice to have a lot of variety– some daylight desert work, nighttime work, aerial work, and urban battle work.

As a sequence supervisor, how many shots did you composite yourself and what were some of the ones we might remember from the movie?

“How many” is a tough question. Let’s say ‘a lot’ (laughs). One of the first ones I did for the show, in fact, one of the first shots finalled, was the initial Blackout transformation– the helicopter transformation that opens the film. Mike Conte handled the lighting and comping of the shot of the chopper’s blades retracting, and Jeff Grebe and I did the big dolly shot of the transformation. It was not only a very complicated CG shot (I mean, the transformation animation is phenomenal and beyond belief), but it was a tough environment reconstruction as well. You see, the real helicopter was in the shot the entire time, so I had to do a full plate reconstruction, effectively erasing the helicopter from the shot. It was made that much more difficult because of the dolly move, as well as all the search lights, fog, smoke, and all of the muzzle flashes from the soldiers who have opened fire on the robot, as well as the airfield, jeeps and soldiers behind the chopper. It was really fun laying in all of those spark hits, though. Jeff did an amazing job lighting the chopper, which is all CG throughout the entire shot.

I also got to destroy Blackout in the end battle sequence, where Josh Duhamel and the F-22’s unload their missiles on the big robot. Those were some tough angles in that sequence (basically, the POV of Josh, sliding underneath Blackout between his legs), but I’m really happy with how they turned out. I did a couple of big Scorponok shots, too, which were really difficult. I’m particularly happy with this one shot of an AC-130 unleashing its firepower on Scorponok from the air. It’s completely cinematic — the guns wouldn’t really produce that much pyrotechnics or tracers — but it works really well within the context in the film.

I’m really proud of the aerial shots, too. F-22’s and Starscream’s air-to-air shots were extremely complicated, and came together fairly quickly. Some of the shots were pieced together out of nothing. I comped almost all of the aerial shots, with two major shots comped by Mark Nettleton. Fred Schmidt lit most of the Starscream/F-22 shots, with particle work from Doug Moore and Jeff Grebe. It was fun coming up with the pipeline and workflow of those aerial shots, since they were their own beasts, fairly separate from the rest of the typical robot shots in the movie.

I helped out on a lot of other shots, too. The ILM team really worked together on this one– there was a great deal of collaboration on Transformers, more so than on any other show I’ve been on. Artists were really willing to do whatever it takes to get things done. And we had a lot of cross-disciplinary work, too. We had compers lighting shots, lighters comping, digital matte artists modelling, paint artists comping, layout artists doing particle work, you name it. It was the most collaborative crew I’ve ever worked with, and I think the final shots really show off the spirit of the show. The animators in particular really stepped up to the challenge, and had overwhelming enthusiasm for this show.

And that’s the only way we could finish the movie. The enormous scope of the film is evident when you start counting all of the characters we had to create and animate; Optimus Prime, Megatron, Ratchet, Bumblebee, Jazz, Ironhide, Starscream, Scorponok, Blackout, Barricade, Bonecrusher, Devastator, Frenzy, and all of the Autobots in their endoskeleton form… not to mention their vehicle counterparts. Not to mention that Bumblebee is two completely different sets of Camaros, so our modellers and creature development folks had to create two versions of robot Bumblebee, and two versions of the CG Camaros. And that’s just Bumblebee.

So we had a great concentration of talent to hit these shots as smartly and quickly as possible. Not to mention, we needed to satisfy one of the most demanding directors in Hollywood, Michael Bay. So, yeah, it was an enormous challenge.

Sounds like you had your hands full. What was your typical day at ILM like?

I personally like to get in early, and make sure my overnight renders worked as expected, with no black frames or goofy errors. Depending on the complexity of the comp, I might be able to squeak out another version of the shot before td/comp dailies at 9am. On a big show like this, dailies could take well over an hour. We look at all the work-in-progress, sequence by sequence in one of our screening rooms. Our effects supervisor Scott Farrar and our associate supervisor Russell Earl then talk about the shots with the artists– and it’s good to have as many people in the room who have similar shots, so everybody can hear specific comments.

For example, if you’re lighting a Bumblebee shot, it’s good to hear the comments from Russ and Scott about other Bumblebee shots, so you have a good idea how to light yours. Every shot is different, but it’s really smart to pay attention to what the supervisors are looking for.

After dailies, I usually check in with TD’s and other compositors, and make sure they know what the day’s priorities are for their shots. Somehow, before lunch, I need to get some takes of my own shots out. After lunch, I’ll work on my shots as much as I can, do some quick rounds, hit a few meetings, and if things are really busy, we’ll attend nightlies (a mini-version of dailies). And before going home, I have to really pay attention to my own shots, because you really want to utilize overnight render time to its fullest. I run as many test frames as possible, to make sure nothing is broken. Just before leaving, I’ll set up my shots to render, and cross my fingers that everything works out okay. Then the next morning, I check on those renders, and it all starts again.

You have been known to be a big advocate of the use of Adobe After Effects for film-quality compositing. Did you get to use AE on Transformers?

Heck yeah. And all on a Mac G4 that ILM got me for Van Helsing, too. There were a couple all-2D shots that I did almost entirely in AE, which is something I like to do at least once on every ILM show I work on. But for several of my shots, even ones with robots, I would use AE’s 3D compositing to generate render passes. I’d bring those renders into Shake and balance them, just as I would my robot renders. It’s the only way I could get these shots done– the fast feedback and interactivity I get in AE is vital to my workflow.

For example, for that first helicopter-to-Blackout transformation shot, I laid out all of the spark events and bullet hits in After Effects. There were dozens upon dozens of little hits, and the only real way to manage and animate them all was to use After Effects, and I could just throw the sparks in 3D space, and not have to worry about any kind of camera tracking. The same with Blackout getting killed– all of those 2D explosions needed to wrap around Blackout’s body in a very specific way, and I had to try out several different elements to get the right one, and each needed special animation. All the pyro for those were set up and rendered out of After Effects.

It’s a trivial process to bring our layout matchmove cameras into After Effects, so if there’s any kind of tricky camera move, and the shot requires a lot of stock elements, like sparks, smoke, dust hits, things like that, I’ll certainly lay out the shot in After Effects and do the final comp in whatever our comp program might be at the time. In our case, it was a Shake show.

I also took it upon myself to be the anamorphic point person on the show, and After Effects played a part in that process, too. Based on all the research I did on Mission: Impossible III, which was also shot in anamorphic, I already had a pretty good library of reference and techniques ready to go. But this film was quite different than MI3, in that Michael Bay uses all sorts of wacky lenses and rigs, regularly underexposes, has more frenetic camera movement than just about any other filmmaker I’ve ever worked for, and regularly aims the camera directly at light sources for effect. And because our main characters, the Transformers, all have light sources on their bodies (headlights and such), we had to be very careful to create very realistic CG lights. Not only the volumetrics and physics of the lights have to be accurate and match the rest of the movie (you know, all of the practical, real light sources, like real headlights, flashlights, streetlamps, etc), but they have to interact with the lens of the camera realistically.

At the very minimum, this means creating realistic lens flares, but also creating the subtle reflections and aberrations that naturally happen with anamorphic lenses, not to mention all of the daylight glints that we need to see off of our shiny robots and cars. So I was the go-to guy for all of that kind of photographic work, which was a lot of fun. It meant really dissecting and analyzing anamorphic films and footage from Transformers, and using existing compositing tools (like AE and Knoll Light Factory) and coming up with new tools to create all these effects. That part of the job was very rewarding.

There’s been a bit of an uproar in the VFX industry recently about studios and production companies pushing towards ever shorter post-production schedules (even with VFX shot counts skyrocketing), leaving VFX houses less time to complete their work. Pirates 3 was one of the more severe recent examples.

It’s crazy, and it’s hard to put one’s finger on the reason why this continues. The studios are really compressing post-production more and more, and it’s really taking its toll on facilities. I mean, there’s that horrible story of an independent producer telling an interviewer if he doesn’t put some small company out of business he’s not doing his job.

Yeah, shows you the respect he has for the people working there. Did you feel any studio pressure?

Our producers do an amazing job at ILM making sure we can do the shots within the timeframe, within our budget. And on that front, our Transformers team did an extraordinary job. Our producer, the brilliant Shari Hanson, and our amazing production manager Peter Nicolai made sure that everything was scheduled properly. Our throughput on Transformers was truly extraordinary, even when the facility was pushed to over-capacity.

Generally speaking, we always wish that we had more time. Ultimately, the scope of our work fit the time we had to accomplish it, but only because we had a stellar team working on the film.

Personally, if visual effects producers hold their ground and not let the studio roll over them (at the risk of losing work to cheaper houses), and prove that they can get the work done with *this* budget and *this* timeline, and the work will be of superior quality, I think we’ll be fine. Like I said, the producing team at ILM and our ILM executive team did an amazing job, in this respect.

What sometimes happens in situations were time is very short is that shots are handed over to another company because the main FX vendor runs out of time. Did any of that happen on Transformers?

As far as I know, we didn’t farm anything out. Digital Domain had a chunk of work from the start, including the meteors that land on earth, Frenzy’s severed head shots, all of the Arctic Circle shots of the discovery of frozen Megatron, and a few others. Personally, I thought DD’s work was really nice, and fit well within the film. Asylum also did some work on the film, but I’m not sure of what their work consisted.

What was the turnaround on a typical Transformers shot?

That’s a tough one. Some of the early shots took quite a while, because we were still trying to figure out how to animate our transformations, and how to light the robots. Some took two or three months from start to finish. Near the end, we were cranking out shots relatively quickly, using what we learned throughout the course of the show, with some shots getting wrapped from start to finish in just a couple of days.

With all the stand-out CG imagery featured in the movie, people tend to forget the huge amount of model work still used in big FX shows like this…

The biggest setup was what we called the Clinica building destruction setup. Megatron flies full throttle at a stationary Optimus Prime down the streets of Mission City (in the end battle), and slams right into him, effectively picking him up and taking him for a ride. They slam through the side of a building (a CG impact and animation), then go right through the full interior of an entire building. In five dramatic shots, they break through huge columns, go through office desks and chairs, all with people running for cover, and emerge from the other side of the building, landing on the street again in a huge pile of debris. The four shots of them going through the building were accomplished with a gigantic miniature building, set up in a couple of different takes and angles. Kerner built approximations of the two robots (which would later be replaced with CG versions) and rigged them up on a track to knock through the building, and roll over miniature desks, chairs, lamps, blinds; the raw footage was pretty remarkable. It was all shot against green, so we could fill in the environment later. We also shot ILM employees against greenscreens to be the office workers running for safety. They had a lot of fun acting, and the compositors had a lot of fun deciding which ILM’er goes where, who runs to safety, who almost bites the dust, and whose fate is ambiguous.

Transformers was, along with Pirates 3, one of the first ILM shows where the model work was handled by the recently split-off Kerner Optical. Did this affect communication in any way?

All of the Kerner guys are such pros, and they handled an amazing amount of quality work for our latest group of ILM movies. They produced an immense amount of work for Pirates 3, Evan Almighty and Transformers, and it all worked out really well. Our effects supervisor Scott Farrar has worked with some of the Kerner guys for decades, so there’s a really nice, comfortable level of communication between us. We’re all so happy that the spinoff has worked out well for Kerner. I hope we continue to work with them on big shows like this.

Were the smaller stage elements like pyro hits and dust blasts shot at Kerner as well?

Our compositing supervisor, Pat Tubach, supervised a few shoots, where we tried to photograph some specific events for the film, like the sabot round bleeding effect (which we used those elements for, but also had CG bleeding, as well), and a few other specific concrete/debris elements for various angles.

But it’s funny– a few times we had to stop ourselves and say, “You know, five years ago, this one shot that I’m working on would have required a special pyro shoot, with motion control, custom blasts, the whole shebang… and now we’re just using our stock library and trying to make it work.” I particularly had that feeling while working on the Blackout death shots, where F-22’s fire upon Blackout, and Josh Duhamel fires a grenade round into Blackout’s crotch. I used two or three of the pyro elements that Pat shot, but the vast majority of the pyro was culled from our massive ILM stock library. I had to, of course, try out dozens and dozens of sparks and explosions until I found the found the right one. That’s a pretty common way of designing these big shots for our compers - a lot of experimentation and trial and error until we get the ingredients just right.

There were full-scale mock-ups of some Transformers built by the production crew (of Bumblebee, in any case). Did they survive into the final cut?

Ultimately, I think the Bumblebee mockup was only used for a few shots, where Bumblebee is unconscious and being sprayed by Sector 7 minions. I think there’s one other shot in the city fight using the mockup, but that’s it. Also, there was a full size Megatron, only built from the feet to his waist, in his standing, frozen pose. Everything above his waist was all CG (including the entire environment). There were also a couple of puppet Frenzy shots in the Air Force One sequence, too. Other than that, every single robot you see in the movie is 100% CG.

You supervised the desert Scorponok sequence. How much of the sand effects were shot on set, and how much were digital / stage elements?

Michael Bay shoots fast, and he shoots dirty. And I mean that he really likes to see the practical effects, even if there will be several robots interacting and moving through those effects. So for nearly every single sequence, we would have plate photography that contains several real explosions, sparks, and a ton of smoke and dirt through the air. The great thing about that, is that you already have a built-in sense of cinematic reality; the downside is that we then need to somehow integrate our robots into that environment (making compositing that much harder), and also have our robots *interact* with those effects. So when a robot runs through a practical smoke element that was actually in the plate, we would have to figure out a way to make that look good. But our compositing and td team was so strong on Transformers, that rarely did we ever shout in disgust, “I wish they just shot this clean!” We’re so used to creating the entire frame, with movies like the Star Wars prequels, or the Harry Potter movies, that it was a refreshing break to do some serious compositing– putting our CG creatures and effects into very, very dirty plate photography, rather than putting our CG creatures into fully synthetic environments. And the end result is exactly what Michael wanted– a gritty, dirty, realistic environment where these robots interact with the world in a plausible way.

In the case of the Scorponok attack sequence, there actually was a great deal of on-set effects work created by John Frazier and his practical effects team. They rigged all sorts of air cannons underneath the sand to push up and out, which gave the actors something to react to, and also give a lot of instant credibility to the shot. The hard part was burying Scorponok inside that sand bomb in a convincing way. We had to add a lot of practical sand effects and do some CG particle sand work, led by Nigel Sumner and John Sigurdson.

What were some of the more invisible effects from the movie, things audiences might have missed?

For one thing, the film was shot all over the country, with its final city battle containing locations in downtown Los Angeles, various studio backlots, and even some shots taken in downtown Detroit. So our digital matte department had to do a lot of set extensions and continuity work to make it seem like these were all of the same world. Richard Bluff was in charge of all of our matte paintings, and did a phenomenal job adding skyscrapers into the background of backlot photography, beefing up LA photography, tying in Detroit photography, and even creating some fully synthetic city environments based on some of the thousands of photographs we took while on location. The shot of Megatron and Optimus crashing through the skyscraper near the end of the film contains a lot of miniature model work, but everything beyond it is purely synthetic. That stuff is always intriguing to me– it’s one thing to make the foreground action believable, but if the backgrounds look wonky, the whole illusion is shot. Michael Bay was always very particular about those background buildings, so it was a challenge. Also, the buildings that Optimus and Megatron skillfully scale down (pretty much destroying two faces of the buildings) are also completely synthetic, as is the world around them– and that goes for a whole series of shots *before* Optimus and Megatron fall down the side of the building. Nearly every rooftop shot has some kind of manipulation or full on matte painting to maintain continuity, since those buildings didn’t really exist. The animation and debris effects in the sequence are wonderful, but the world needed to look plausible and realistic to truly sell the effect.

I like little things, invisible effects, that people might not even recognize. There’s a relatively quiet shot of Blackout, just after he’s landed in the city fight, of him revving up his propellor, threateningly, while slowly approaching Optimus and Megatron. We’re looking over some soldier’s shoulder, while Blackout menacingly powers up his propeller. The compositor, Mark Nettleton, noticed that the animator put the propeller close to a “No Parking” sign, at least in screen space. Mark erased the sign, then re-tracked it back into the shot, and did some nice little 2D animation to make it appear as though Blackout ripped it to shreds. It was really sweet, and we pretty much used his first take of that animation. We just loved looking at it over and over. It’s something that people might easily miss (I mean, everyone is pretty much watching the giant robots), but it’s stuff like that that really helps make a shot special.

So, after the marathon that was Transformers, what’s next for you?

I’m in the middle of a sweet, long vacation. Well, not really a vacation; my wife and I had our first baby a few weeks ago, so my new job is Dad. It’s absolutely fantastic, and insanely insane at the same time. When I get back, I don’t know what my next big show will be. It looks like we’ve got some really big projects on the horizon, and I can’t wait to get going on them.

Being Dad will certainly turn out to be your biggest but most rewarding project yet, and we here at VisualFXBlog.com wish you and your family all the best.

Thanks for the interview, and we look forward to more exciting projects!

Visit Todd Vaziri’s Blog, FXRant, for more information about the work he did for Transformers and a whole lot more!

Also, check out ILM’s official site as well as the official Transformers Movie site.

Images Copyright © 2007 DREAMWORKS LLC and PARAMOUNT PICTURES. All Rights Reserved.

back to Professional